From snow-capped volcanoes to green sand beaches, Hawaii’s reputation as exotic is nothing if not duly earned. Far more than the fabled seaside beauty often rendered in postcards, the 50th state is a place filled with tremendous surprises and incredible diversity.

One of its many marvels is found neither on the sand nor in the sea: The ʻōpeʻapeʻa—or Hawaiian Hoary Bat—is an endangered species that swoops from the rainforests to the clouds above the islands’ famed beaches.

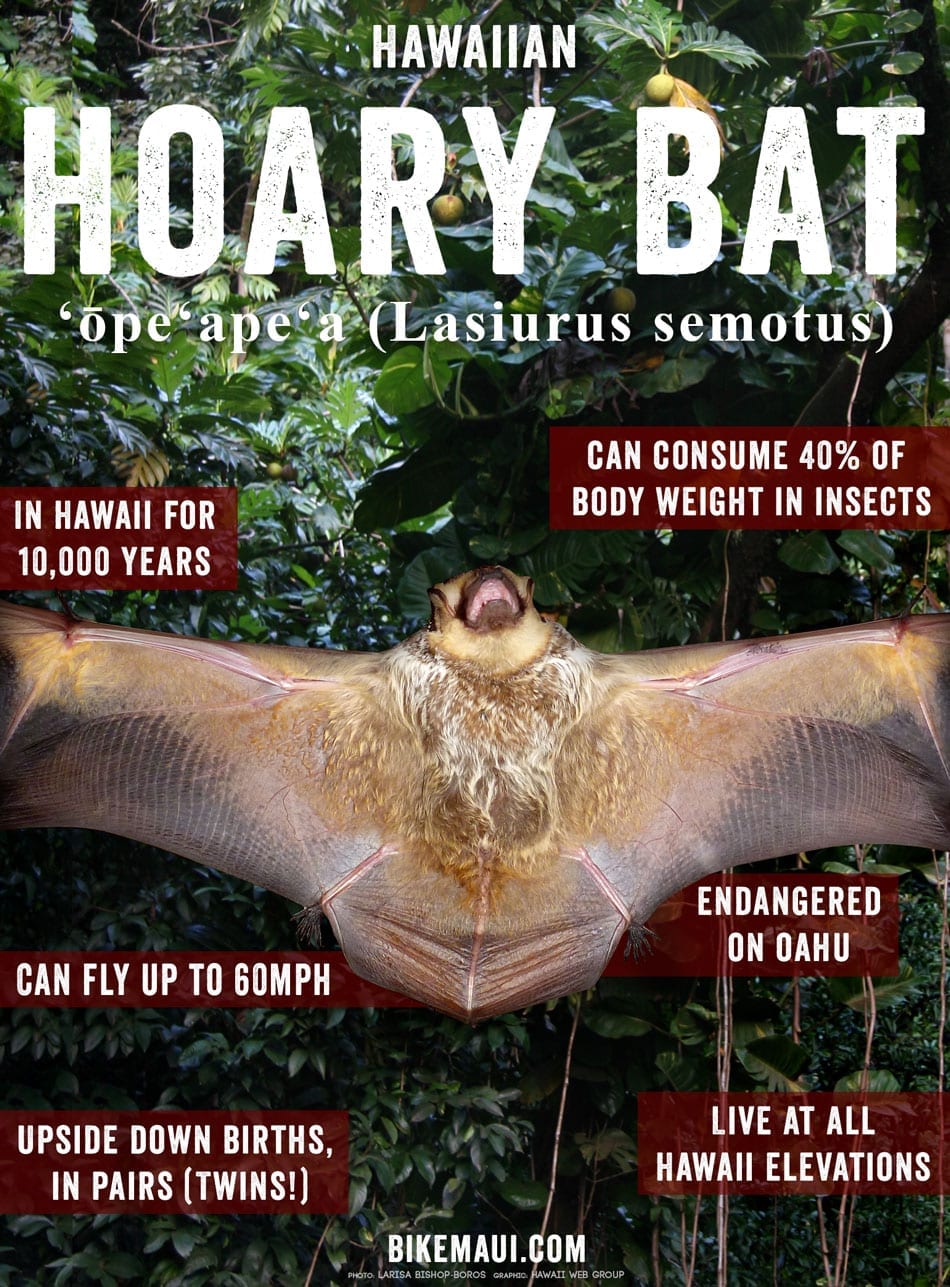

Weighing in at less than a mouse, the Hawaiian Hoary Bat is one impressive creature.

Once thought to have arrived in Hawaii with the initial human visitors, research now suggests that the ʻōpeʻapeʻa existed prior to the first footprint on the islands’ golden shores, with fossils showing its presence in Hawaii as far back as 10,000 years ago. Given that Hawaii is 2,300 miles from the nearest landmass—rendering it the most isolated chain of islands in the world—these tiny, winged beasts had to migrate for massive stretches above the wide, open sea. Unlike birds, bats don’t usually travel for thousands of miles, leading some scientists to surmise that the ʻōpeʻapeʻa arrived with spectacular, wind-wild storms. However they arrived, one thing is for sure: Their presence in Hawaii is an enormous feat, representing the survival instinct at its finest.

Unlike its cave-dwelling cousins on the mainland and beyond, the Hawaiian Hoary Bat takes to Hawaii’s skies like a sunbather to the beach, preferring lush rainforests to dusky caverns and taking shelter in ‘ohia, kiawe, coconut, and kukui nut trees.

While smaller than its North American kin by roughly 30%, the ʻōpeʻapeʻa lives up to its ohana’s legendary status as a creature of the night. Nocturnal and sharp-toothed, the Hawaiian Hoary Bat is found from sea level to the islands’ loftiest volcanic peaks, vacating its lodgings only at sunset and returning home just before sunrise.

And hoary it is:

Ladies and gents alike possess tan, reddish-brown, and silvery coats that, like Mauna Kea, are tipped in white. Its name is inspired by its image in flight, which native Hawaiians attributed to the appearance of canoe sails and the bottom half of their much-celebrated taro leaf.

Long considered a subspecies of the forest-friendly hoary bat of North and South America—the most ubiquitous bat in the contiguous United States—the ʻōpeʻapeʻa is now deemed a separate genus, making it one of only three species endemic to the Hawaiian Islands.

Much like the pueo—a rare Hawaiian owl with great spiritual significance—the ʻōpeʻapeʻa has become dramatically decimated on Oahu, where natural habitats have waned as the island’s population has expanded. While it’s still up in the air whether pesticides are partly to blame, its decline spurred the bat’s precautionary inclusion on the list of endangered species in the 1970s. Threats against their existence span from deforestation and predation to collisions with wind turbines and barbed wire fences—a reminder that these creatures once roamed the Earth largely without human influence. In a call for recovery, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service devised a plan for resurgence that includes careful monitoring of echolocation, a communication method used by bats, dolphins, and whales for navigation and hunting.

Female ʻōpeʻapeʻa have a slight advantage over their male counterparts, with a larger wingspan and slightly bulkier physiques.

Consider it nature’s way of equipping them well for breeding multiples: The Hawaiian Hoary Bat gives birth in pairs, with twins popping out in summer. Blunt-nosed with thick thumbs, this is indeed a species that’s guided by the seasons, with their mainland pals separating throughout the year when females take to the lowlands and coastal valleys during winter while males flock to the foothills and mountains. Back in the islands of the Pacific, males and females court in autumn flight, a complex dance that’s followed by delayed fertilization—a process in which sperm is stowed until fertilization occurs in spring.

Consider it nature’s way of equipping them well for breeding multiples: The Hawaiian Hoary Bat gives birth in pairs, with twins popping out in summer. Blunt-nosed with thick thumbs, this is indeed a species that’s guided by the seasons, with their mainland pals separating throughout the year when females take to the lowlands and coastal valleys during winter while males flock to the foothills and mountains. Back in the islands of the Pacific, males and females court in autumn flight, a complex dance that’s followed by delayed fertilization—a process in which sperm is stowed until fertilization occurs in spring.

Births are a spectacle to behold, with the ʻōpeʻapeʻa hanging upside down from trees as their progeny make their way into the world.

Despite their ability to fly at speeds of up to sixty miles per hour, the Hawaiian Hoary Bat is a fragile creature at birth. Newborns cling to their mothers throughout the day for their first six weeks and latch onto branches when their moms take off at night to retrieve groceries. Come near an infant and its mother will make a rather feline fuss: When troubled, the ʻōpeʻapeʻa lets loose a high-pitched hiss. And this bashful, dark-eyed beauty prefers its own company: It roosts in solitary under the dense canopy of trees.

Such isolation explains part of its alluring mystery.

Its solitary habits—coupled with its diminutive size and penchant for forests, lava tubes, and cliffs—makes it challenging to see and often only joins others when foraging for food.

Hunts bring a good harvest in insect-rich Hawaii, with moths comprising the heft of the ʻōpeʻapeʻa’s diet.

Their attack is quiet and deadly—they approach and feast from behind before dropping their prey’s head. But think of it as less of a brutal act than an innate part of ecology: As “insect consumers,” bats play a critical role in the balance of Hawaii’s bionetwork by keeping mosquito, cricket, beetle, and termite populations in check. And avid consumers they are: The Hawaiian Hoary Bat possesses the ability to consume 40% of its body weight in insects over the course of a single night.

Confirmation of interisland migration remains elusive but scientists have observed its occurrence on all of the major islands except for Kaho’olawe and Ni’ihau.

The ʻōpeʻapeʻa seeks the higher elevations of the islands’ volcanic slopes during the winter months, which provides them with cooler climes that promote a more efficient resting metabolism. Not to be confused with the Mariana Fruit Bat of Guam or Samoa’s Pacific Sheath-Tailed Bat, the Hawaiian Hoary Bat reached celebrity status when Governor Ige appointed it the official state land mammal in 2015—a title that brings the pocket-sized animal into company with the Humpback Whale, Kamehameha Butterfly, Monk Seal, and Humuhumunukunukuapua’a, Hawaii’s vibrant state fish.

Determined to see the ōpeʻapeʻa glide across the sky? Keep your eyes peeled at sunset and, for once, pray to be blind as a bat: Despite the popular idiom, these mammals have superior vision.

Thank you to Haleakala Eco Tours for this informative article!